In my last blog,

a cloud of two speeds, I mentioned

Vivek Kundra’s very readable cloud strategy and the industry stimulus effect this approach can have on the emerging cloud industry. By presenting his strategy not simply as a way to cut costs and reduce budgets, but as a way to get more value from existing IT investments, he enlisted IT as an ally to his plans, instead of a potential opponent. Section two of the strategy is a pragmatic 3 step approach and checklist for migrating services to the cloud which can also be valuable for organizations outside the government and outside North America.

The following is a short summary of this “Decision framework for cloud migration”.

The full Federal cloud computing strategy (43 pages and available for download at www.cio.gov) includes a description of the possible benefits of cloud computing, several cases, metrics and management recommendations. A short review of the document was given by Roger Strukhoff at sys-con

Decision Framework for Cloud Migration

The following presents a strategic perspective for thinking about and planning cloud migration.

|

Select

· Identify which IT services to move and when

· Identify sources of value for cloud migrations: efficiency, agility, innovation

· Determine cloud readiness: security, market availability, government readiness, and technology lifecycle

|

Provision

· Aggregate demand where possible

· Ensure interoperability and integration with IT portfolio

· Contract effectively

· Realize value by repurposing or decommissioning legacy assets

|

Manage

· Shift IT mindset from assets to services

· Build new skill sets as required

· Actively monitor SLAs to ensure compliance and continuous improvement

· Re-evaluate vendor and service models periodically to maximize benefits and minimize risks

|

A set of principles and considerations for each of these three major migration steps is presented below.

1. Selecting services to move to the cloud

Two dimensions can help plan cloud migrations: Value and Readiness.

The Value dimension captures cloud benefits in three areas: efficiency, agility, and innovation.

The Readiness dimension captures the ability for the IT service to move to the cloud in the near-term. Security, service and market characteristics, organisation readiness, and lifecycle stage are key considerations.

Services with relatively high value and readiness are strong candidates to move to the cloud first.

Identify sources of value

Efficiency: Efficiency gains come in many forms. Services that have relatively high per-user costs, have low utilization rates, are expensive to maintain and upgrade, or are fragmented should receive a higher priority.

Agility: Prioritize existing services with long lead times to upgrade or increase / decrease capacity, and services urgently needing to compress delivery timelines. Deprioritize services that are not sensitive to demand fluctuations, are easy to upgrade or unlikely to need upgrades.

Innovation: Compare your current services to external offerings and review current customer satisfaction scores, usage trends, and functionality to prioritize innovation targets.

Determine cloud readiness

In addition to potential value, decisions need to take into account potential risks by carefully considering the readiness of potential providers against needs such as security requirements, service and marketplace characteristics, application readiness, organisation readiness, and stage in the technology lifecycle.

Both for value and risk, organizations need to weigh these against their individual needs and profiles.

Security Requirements include: regulatory compliance; Data characteristics; Privacy and confidentiality; Data Integrity; Data controls and access policies; Governance to ensure providers are sufficiently transparent, have adequate security and management controls, and provide the information necessary

Service characteristics include interoperability, availability, performance, performance measurement approaches, reliability, scalability, portability, vendor reliability, and architectural compatibility. Storing information in the cloud requires technical mechanism to achieve compliance, has to support relevant safeguards and retrieval functions, also in the context of a provider termination. Continuity of Operations can be a driving requirement.

Market Characteristics: What is the cloud market competitive landscape and maturity, is it not dominated by a small number of players, is there a demonstrated capability to move services from one provider to another and are technical standards – which reduce the risk of vendor lock-in – available.

Network infrastructure, application and data readiness: Can the network infrastructure support the demand for higher bandwidth and is there sufficient redundancy for mission critical applications. Are existing legacy application and data suitable to either migrate (i.e., rehost) or be replaced by a cloud service. Prioritize applications with clearly understood and documented interfaces and business rules over less documented legacy applications with a high risk of “breakage”.

Organisation readiness: is the area targeted to migrate services to the cloud pragmatically ready: are capable and reliable managers with the ability to negotiate appropriate SLAs, relevant technical experience, and supportive change management cultures in place?

Technology lifecycle: where are the technology services (and the underlying computing assets) in their lifecycle. Prioritize services nearing a refresh.

2. Provisioning cloud services effectively

Rethink processes as provisioning services rather than contracting assets. State contracts in terms of quality of service fulfillment not traditional asset measures such as number of servers or network bandwidth. Think through opportunities to :

Aggregate demand: Pool purchasing power by aggregating demand before migrating to the cloud.

Integrate services: Ensure provided IT services are effectively integrated into the wider application portfolio. Evaluate architectural compatibility and maintain interoperable as services evolve within the portfolio. Adjust business processes, such as support procedures, where needed.

Contract effectively: Contract for success by minimizing the risk of vendor lock-in, ensure portability and encourage competition among providers. Include explicit service level agreements (SLAs) with metrics for security (including third party assessments), continuity of operations, and service quality for individual needs.

Realize value: take steps during migration to ensure the expected value. Shut down or repurpose legacy applications, servers and data centers. Retrain and re-deployed staff to higher-value activities.

3. Managing services rather than assets

Shift mindset: re-orient the focus of all parties involved to think of services rather than assets. Move towards output metrics (e.g., SLAs) rather than input metrics (e.g., number of servers).

Actively monitor: actively track SLAs and hold vendors accountable, stay ahead of emerging security threats and incorporate business user feedback into evaluation processes. And track usage rates to ensure charges do not exceed funded amounts “Instrument” key points on the network to measure performance of cloud service providers so service managers can better judge where performance bottlenecks arise.

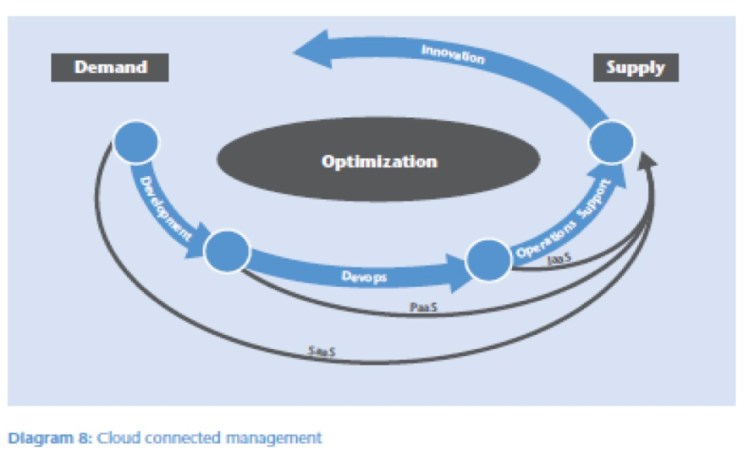

Re-evaluate periodically the choice of service and vendor. Ensure portability, hold competitive bids and increase scope as markets mature (e.g., from IaaS to PaaS and SaaS). Maintain awareness of changes in the technology landscape, in particular new cloud technologies, commercial innovation, and new cloud vendors.

Disclaimer: This summary uses abridgements and paraphrasing to summarize a larger and more detailed publication. The reader is urged to consult the original before reaching any conclusions or applying any of the recommendations. All rights remain with the original authors.